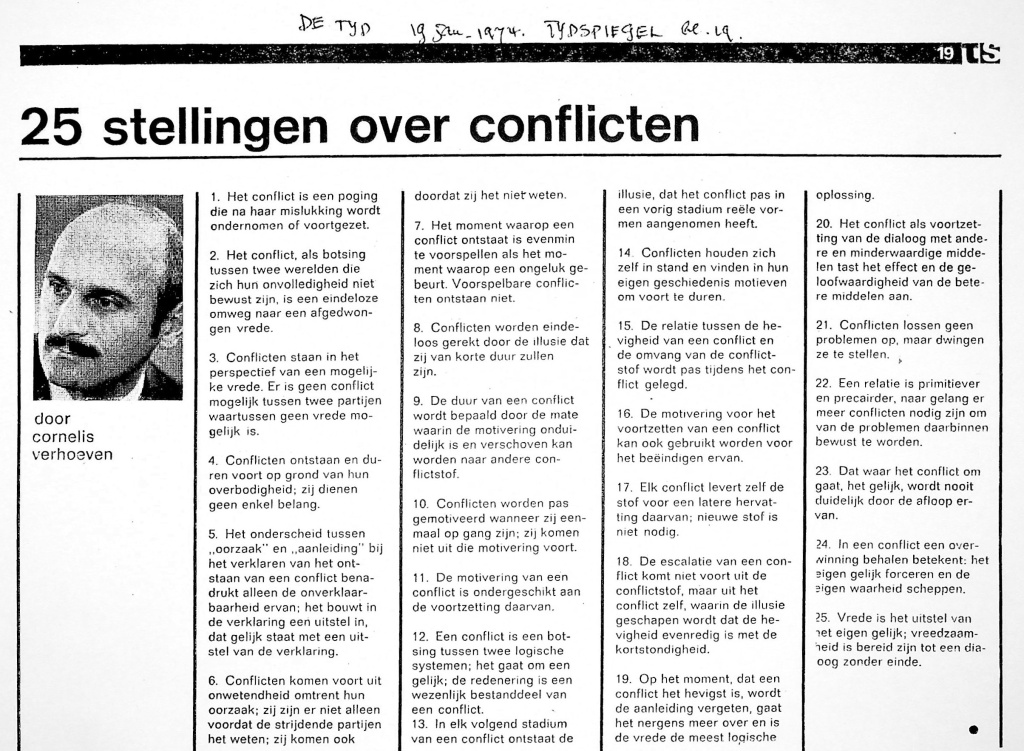

There are probably few people who would be 100% happy to be called ‘good’. Because we often call someone a good person because there is little else to say about him. And strangely enough, this goodness, the absence of all evil, doesn’t have a very favourable meaning. It is pretty much regarded as simpleness. The word ‘simple’ also used to mean: good and innocent and now only means: stupid and unworldly. The world to which the simpleton is alien does not seem to take pure goodness seriously and therefore prefers to give its names an unfavourable meaning. What is not good and bad at the same time, or rather: what, in addition to being good, is not at the same time useful, pleasant, fascinating or admirable, is pushed into a corner by the bad world. Only the ambiguous mixture of good and evil or good and whatever can endure. The pure is not welcome. In the game of the world everything must also contain its own opposite, because each player must take into account all the movements of his opponent. Otherwise he won’t play along and becomes unworldly or silly.

This now also seems to be happening to nonviolence. In everyday language, this name seems to suggest an attitude that ignores the existence of violence. And there is violence, so that attitude is simple, albeit noble and good. Nonviolence is then the noble but unreal attempt to create, in the midst of a world full of violence, an island that is characterized by the absence of the most worldly and is therefore very unworldly.

Now one can of course say that it is not so bad to be unworldly; one can continue to preach noble nonviolence in the face of ridicule. There is something beautiful in that.

But besides the fact that it is difficult to prove that unworldliness is not a bad thing, there is the danger that one will make a virtue out of enduring that ridicule and thus harm the ‘world’ in a stupid way. That does not benefit the world and the purpose of a virtue is precisely that it does benefit the world.

Those who advocate nonviolence should take a different path. They must begin to remove its ‘image’ from the sphere of sterile simplicity. Nonviolence is not at all the same as pure nobility. It is not a denial of violence, but only a refusal to cultivate violence by adopting the rules of the game. It does not coincide with pure goodness.

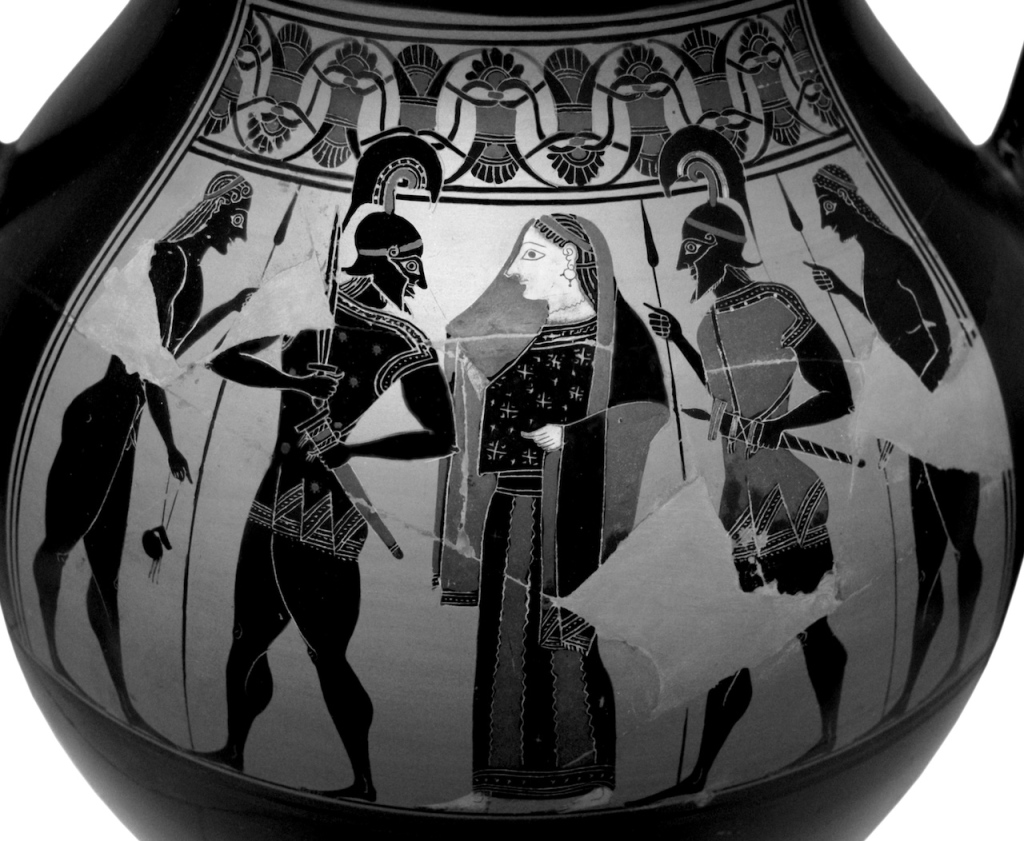

Nor is violence the only evil in the world. And nonviolence should not be seen as a lack of resources. This is often done based on the belief that violence is a super means. But violence as a means is actually very dubious and nonviolence can be very superior from the point of view of the use of means. There are forms of nonviolence that are far smarter, infinitely more evil, and even incomparably more worldly than the primitive and brutal violence they are opposed to. Nonviolence is the human tool par excellence.

And it is not at all true that violence can only be met with violence. Whoever can answer it more effectively is not simpler than the other who uses violence, but on the contrary much smarter. Nonviolence is always superior to violence. Violence is powerlessness; nonviolence can be power. But nonviolence is not superior – this must be especially emphasized – because it contains a heavier element of ethical nobility, patience and gentleness. I emphasize this not to belittle these virtues and push them away into the corner of simpleness, but to highlight the inherent character of nonviolence by removing from it what a hostile and simple world has wrongly placed on it. Nonviolence is characterized not so much by a noble aversion to violence as by the presence of other and more superior means or, failing that, the refusal to do anything, no matter what. The principle of nonviolence means that we do nothing when we have no means; the principle of violence is that the absence of means is never recognized.

The negative name therefore does not indicate a perhaps noble and very difficult attitude towards violence, but an attitude towards a difficult matter. Seen in this way, nonviolence is a ‘technical’ rather than an ethical matter and in any case it does not owe its ethical superiority to its simpleness, but to the fact that it knows how to use means in a situation where others, in the absence of all means, see reason to engage in violence. Nonviolence is the possession of means or, in their absence, expertly practiced passivity, while violence is the simultaneity of an urge to act and a lack of means. Nonviolence can only come from the ability to analyse a situation, while violence is the unwillingness itself to analyse. It will be clear that the first attitude is far superior. Ultimately, this consideration is not enough to make the better attitude prevail on all fronts, but my intention was only to show that nonviolence has nothing to do with stupidity, and on the other hand, violence has everything.