(editorial written during the 6 day war in 1967)

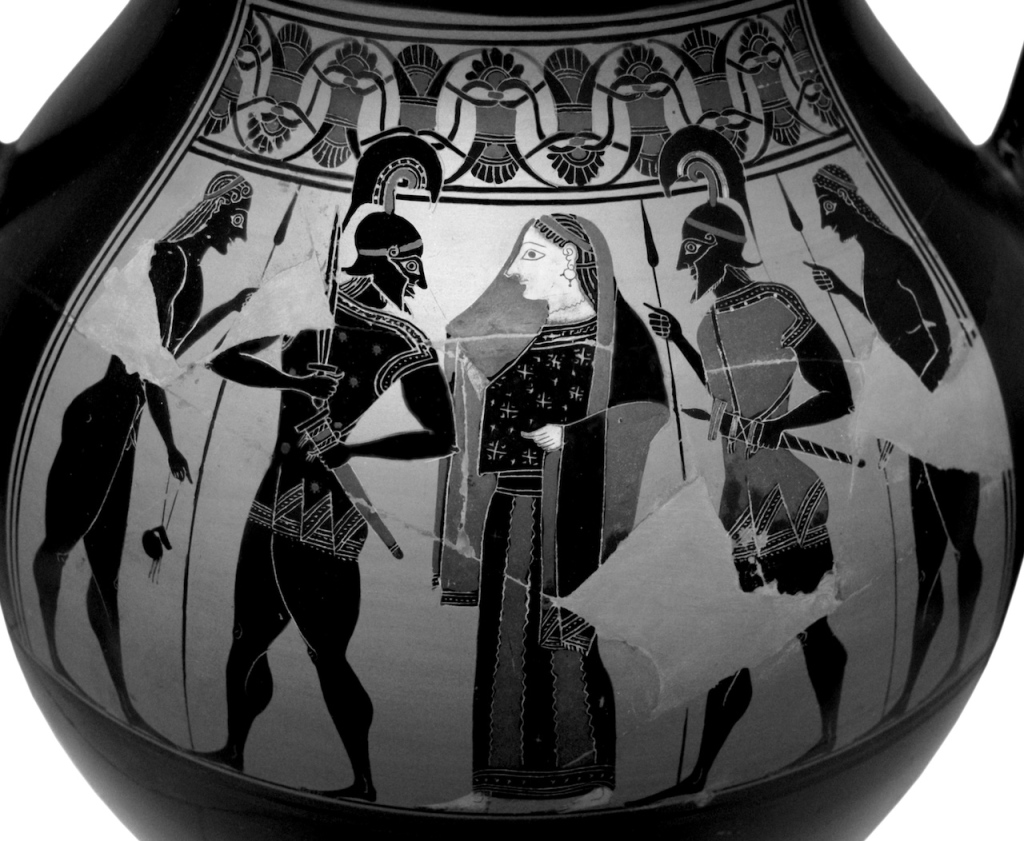

According to the well known Greek saga, Helen, wife of the Spartan king Menelaus and famed around the world for her beauty, was kidnapped by Paris, who had gained the permission and courage for this by Aphrodite, the goddess of love. The elopement then became the cause for the Trojan war. For Menelaus and his brother Agememnon gathered a large number of Greek heroes and sailed across the sea to Troy to avenge the injustice. Only after a ten years siege did they manage to take the city by means of a ruse, the well known wooden horse that, filled with soldiers, was brought into the city.

That is a saga, something that’s being told and something to talk about. A large chunk of Greek literature finds it starting point in this saga. But it can also be discussed differently than from a literary point of view, for example critically. Herodotus, a Greek historian from the fifth century before Christ, does this. In his work we find a different reading of the Trojan saga, recorded from the mouths of Egyptian priests. When Paris had kidnapped Helen and wanted to sail away from Greece, an unfavourable wind was blowing which made him end up in Egypt. And the Egyptian king took Helen under his guard, along with the possessions Paris had robbed, so that Aphrodite’s favoured had to sail back to Troy alone. When the Greeks landed there and demanded Helen, the Trojans could rightfully say that she wasn’t there. Of course nobody put any faith in their words and only after the city was conquered did it turn out they had spoken the truth, and that the whole ten year war had been a senseless undertaking. Herodotus, who takes this saga rather seriously, says that this reading strikes him as the most believable. For, as his reasoning goes, if the Troyans really had Helen in their midst, they wouldn’t have been so insane to endure a long and bloody war just to give frivolous Paris the chance to have an adulterous love life. They would have handed over Helen.

This argument does sound convincing. It’s just that, if you are busy anyway looking at this saga critically and trying to learn from it, then you also have to say this: if Helen truly was in Egypt and not in Troy, then the fight was even more senseless. For then, there wouldn’t have been any stakes, not even the protection of the adulterer Paris. We then reach the conclusion that the Trojan war, the most sang about war in history, the first conflict between East and West, either had as its stakes something as frivolous as the love life of cowardly Paris, or nothing at all; with the footnote that, the longer we look at the affair critically, the probability increases that it was about nothing at all, at most that nothing that we can call a ‘miscommunication’.

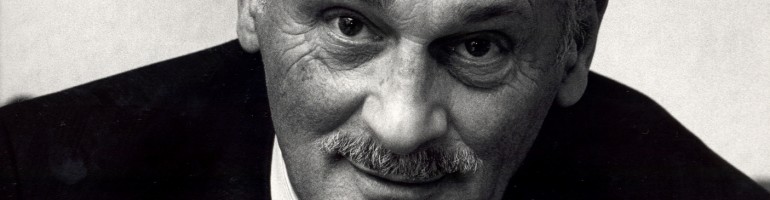

Ernst Bloch wrote extensively about this allegorical meaning of Helen in Egypt in his colossal work “Das Prinzip Hoffnung”. “There were you are not is where happiness is” says Bloch. Dreams invite to distant journeys and long detours. In every conception there’s an element of hope, that in its own way and despite reality stubbornly remains. Even though Helen is in Egypt she has to be in Troy, for there is where the battle rages. And vice versa: if there’s fighting in Troy, Helen is in Egypt. The dreamt version of Helen beats the real version. I believe that our surprise about this situation gives us all kinds of connections to current events. Helen is once again in Egypt. The stakes of a heroic and what’s even called idealistic battle withdraw themselves again from the possibilities that can be realised by war. In war it always turns out to be about ‘something else’ and in that, war isn’t different from a domestic fight. The effect is in no way related to what the war was meant to achieve. Helen is in Egypt, while they’re fighting about her in Troy.

Only after the war does it turn out to be the same Helen. But when we deduct from the dream vision what the intoxication has added to it, than that same remaining reality has only become more problematic. The problem of why the war started, has become twice as big, and lays the foundation for yet another more violent war which in turns increases the problems. For example: one of the causes of the war in the near East was the large number of Palestinian refugees. That number hasn’t decreased; on the contrary it has increased with thousands of Jordanian refugees. The animosity which brought forth this war has also not gotten smaller: it has, historically speaking, been prolonged by at least one generation. The chance of a new war has only gotten bigger.

To draw from this the conclusion that nothing can be achieved with war, seems to me especially weak and untrue. Some things can indeed be achieved by it. It is an iron law, that war achieves the opposite of what it intended to do. War is an extraordinarily efficient, even an infallible means to, at the costs of unimaginable sacrifices, achieve what we would like to avoid at all costs; it is the only truly efficient way to turn difficult problems into unsolvable problems.